Rethinking Mineral Life in the Atacama

Chile - London, 2019

Re-thiking Mineral Life is part of an ongoing research about minerals and extractive processes from the Atacama Desert in Chile that presents minerals as natural and cultural carriers of histories and local narratives. With the purpose of re-thinking the value of disregarded minerals and mining waste, the project started as a site-research project investigating saline minerals through the local landscape and mining history of the Atacama Desert. Going from open salt flats, to nitrate lands of the ‘saltpetre era’, salt mine pits, iodine and lithium evaporation ponds, this research went through different mineral landscapes that are somehow interwoven with forgotten and hidden stories.

‘Salt Imaginaries; Rethinking Mineral Life in the Atacama’ was developed during the Designers in Residence Programme at the Design Museum in London, which started with a 10-day research trip to the desert that aimed to explore salt flats and their geological and extractivist histories. The investigation was exhibited with an installation, a film, and a publication with a critical essay reflecting on minerals as creators of the universe.

Estación Lagunas, Tarapacá.

Salar Grande, Tarapacá

Abandoned open salt pit in Salar Grande, Tarapacá

Salar de Atacama, Antofagasta

Archeological site in Cumiñalla, Tarapacá

Mine tailings on the road, Antofagasta

The Atacama is the driest desert in the world. Its extreme conditions have fossilised the landscape, which is covered by a saline crust. Chilean history has been shaped by mining since ancestral times, but due to limited resources, bad regulations and waste, we are now facing environmental challenges that will force us to reshape the ways in which we extract resources and inhabit extreme landscapes. Mining produces a huge amount of waste and disregarded minerals, in which tons of salts are discarded in lithium refining processes or left as residues on the road from the salt mines to the port.

The trip was structured into two main expeditions —to the regions of Tarapacá and Antofagasta— exploring different salt crusts, microbial ecosystems, mining settlements and mineral residues. Led by local guides, geologists, and researchers, we travelled around the desert documenting the landscape, taking samples and talking from sunrise to sunset about the beauty of minerals, the history of the Andes, indigenous cosmologies and current corporate corruption.

‘The properties of materials are not attributes but histories’ 1

—Tim Ingold

Today, we are living in the era known as the Anthropocene – a geological epoch marked by human dominance over planetary existence. This overpowering force has come to have an impact on life at geological, meteorological and biological scales, and has led to the rapid extinction of other species. Within this contemporary context, we have come to categorise the world into life and non-life, drawing dividing lines between what we see as organic and inorganic, human and non-human, natural and synthetic. Design practice can often be conceptualised within these same categories, reducing the ‘material world’ to one that is inert and manufactured, where objects and materials function as commodities. But if we zoom in, or look back, we will hear them moving, breaking, growing, stretching and shrinking, changing and changing us.

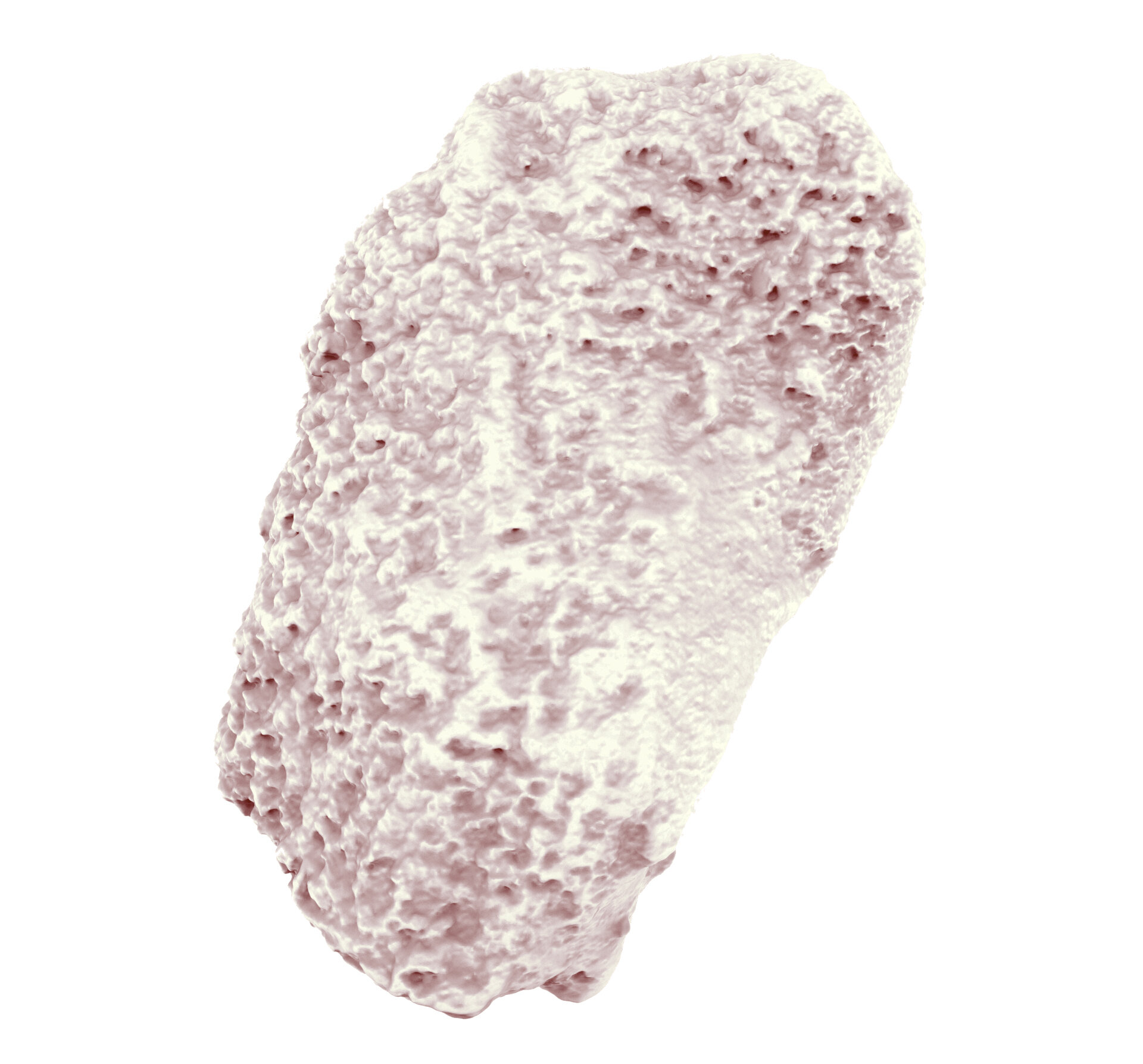

Earth’s geological layers and material resources are in constant flux. When looking back at the history of evolution, it is evident that nature and geology have had a far greater impact on the planet than humans. This becomes particularly apparent when exploring mineral evolution. Minerals take us back to the origin of the cosmos. They are inorganic natural formations, resources for human processing, raw materials, heavy rocks and precious metals, and they were creators of the universe. To study minerals is, in a way, studying the formation of human history. Their materiality teaches us about the mysteries of the Big Bang, and other interplanetary connections, as well as the current environmental and humanitarian challenges that the Anthropocene presents.

It was through mineralisation processes that a new material for building living structures emerged: bones. Long before our bones were shaped, minerals shaped the land we would later come to extract them from. In the Atacama Desert, these natural and cultural carriers are much more than rocks in a hostile landscape: they are active agents that have shaped territories, civilisations and ecosystems for rich microbial life. In the desert, minerals can teach us about Andean cosmologies and the ongoing history of resource extraction.

*Introduction from essay ‘Salt Imaginaries; Re-thinking mineral life in the Atacama’, written by Mále and published in the book ‘Cosmic Designers In Residence 2019’ at the Design Museum, London 2019.